|

STONE ARCH BRIDGES

1914 Kay 36N3390E0090002 Mike Herber

1916 Pushmataha 64N4137E1870003

1918 Love 4314 0270 X

1918 Murray 5030 0252 X

1930 Kay 36E0255N3310003

1930 Mayes 49E0610N4390007 US Dept. Interior (BIA)

1934 Pontotoc 62N3570E1550001 Civilian Conserv. Corps

The success of concrete and steel spans, along with their cost effectiveness in meeting the needs of Oklahoma highway builders, relegated stone arch structures to a minor role. In many places stone found use in making culverts or building abutments for trusses, and it proved a durable and attractive material, but stone bridges required a handy source of supply and fair amount of labor, including skilled workers. Those bridges which were built often originated at the local level. County officials wanting permanent, low-maintenance structures to cross minor streams on farm-to-market roads contracted for stone bridges when the material and a qualified work force were available. In those instances it made sense to use masons and local quarries for constructing bridges.

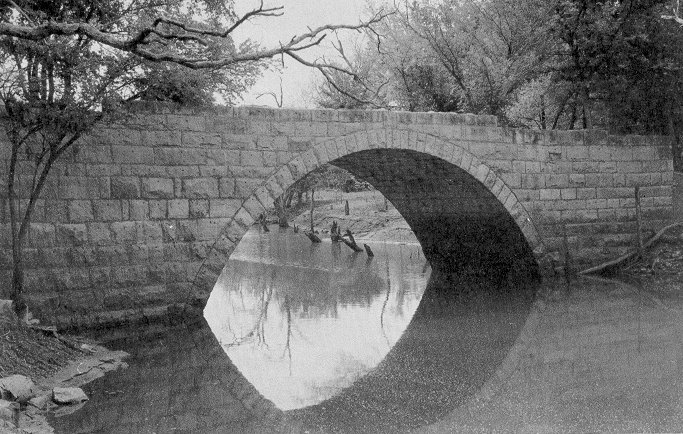

Figure 79. The quality of building material in the stone quarries of Kay County attracted skilled masons. That workmanship is evident in Bridge 36N3390E0090002 which is located east of Newkirk.

|

|

These conditions existed in north central Oklahoma and enabled Kay County to erect some stone arches, drawing on the same craftsmen whose stonework is evident today in the towns of Ponca City, Blackwell, and Newkirk. The county generally purchased trusses, but in 1914 it entered a contract with stonemason Mike Herber to build an arch bridge over Wolfe Creek near Newkirk for the sum of $2,009.40 (Figure 79). The rockfaced structure fashioned of coursed-limestone blocks and with flared wing walls at both ends displays a high degree of craftsmanship that is not typical of rural bridges.

In the same period (1916) Pushmataha County added an attractive, single span, sandstone arch bridge across a creek north of antlers on a rural road. Built with a low curb that primarily acts to mark the edge of the road as opposed to a more substantial parapet rising from the spandrel wall, this feature is common for such bridges which at an earlier time might have had only a simple wooden or steel railing. Counties were careful not to create barriers restricting the movement of wide farm implements. At 60 feet in length, this span and the Wolfe Creek bridge are the longest stone arches in the state.

The construction of stone arches, particularly for their rustic qualities in scenic areas, revived during the 1930s as a consequence of depression-era work relief programs that encouraged greater use of manual labor. The expense of labor had been a prime factor in limiting the construction of this bridge type. Federal make-work programs often focused on road and bridge projects, and Oklahoma benefited from this emphasis. New Deal projects affected many bridges in the state including renovation work on stone bridges on scenic highways in the Arbuckle Mountains and nearby Lake Murray. The rubble stone bridge at Lake Murray is an attractive asset in this recreational area, the structure having well-blocked ringstones and a prominent, elongated keystone (Figure 80).

The Civilian Conservation Corps proved the most active federal agency in building stone bridges in parks and wilderness areas. In 1934 this agency helped the city of Ada construct Wintersmith Park, a recreational facility located at a lake near the campus of Eastern Oklahoma State University. Workers employed by the CCC built a lodge, bathhouse, and a 38-foot bridge out of stone cut from local quarries. The one span bridge made of coursed rubble has four raised end posts capped with stone. Heavier blocks formed the arch ring (Figure 37).

Elsewhere in the state during the depression the federal government assisted the unemployed through such agencies as the Bureau of Indian Affairs. In one case Cherokee Indians worked under the supervision of Mayes County engineer to erect a limestone arch over a stream south of Locust Grove. Although a mere 21 feet long with a low curb, it stands high above the creek, and the carefulness of the work is evident in the squared stone spandrel walls that required only minimal amounts of mortar (Figure 81).

The 171 bridges chosen for their potential eligibility to the National Register of Historic Places reflect the extent and diversity of structural types in Oklahoma. Based on a Comprehensive inventory and evaluation, these spans were found to have the qualities of historical and technical merit that make them outstanding examples of bridge building. While individually they rank as significant of how the highway system evolved to meet the needs of a growing state during the twentieth century. Thus, these bridges form an important chapter in Oklahoma history and a valuable part of its built environment.

Figure 81. A depression-era project which employed Cherokees from the area, Bridge 49E0610N4390007 is a stone arch south of Locust Grove in Mayes County.

|